It’s polling day here in the UK, and so many of us will be off to put our x’s in the boxes (I would like to say most of us but the number of people who actually bother to go out to vote have been woefully low in recent years; personally I think it should be compulsory to vote – even if you just spoil your ballot paper in protest at the non-inspiring choices). This has been an interesting election for one reason only – no-one knows what the outcome will be. It’s too close to call between the Conservatives and Labour to win the larger percentage of the vote, and whoever does win will almost certainly then need to form some sort of coalition if they are going to get anything done.

So, it’s been fascinating for that reason – but the campaigns haven’t exactly set the world alight. For the Tories, it’s been “all about the economy, stupid”. Labour have tried to imply that not voting for them would mean the death of the National Health Service. The honest truth is that it’s impossible to KNOW the truth – you can vote for who you THINK will make less of a mess of it, but really it’s anyone’s guess as to how the next few years will pan out.

In the meantime, one of the things this election hasn’t been about is foreign aid. Well, it has – but perhaps not overtly, in the same way as the economy, health and education have tried to grab our attention.

Foreign aid in this country has been ring-fenced during this parliament and, to be honest, we should be proud of the fact that we do contribute more per GDP than most countries. But, there are many – and at least one main party (UKIP) – who think we should do away with foreign aid altogether, that the money would be better spent back here in the UK on our homeless, our malnourished children, our poorly educated and our destitute. However, I think what people possibly don’t realise is that foreign aid, ultimately, helps not just the people in some far-off land, but themselves as well. I think the problem is that the people who “do” foreign aid just aren’t very good at explaining it properly.

So, as some of you reading this head off to the polls this morning, let me do my best to explain why keeping our foreign aid budget is a good thing. In my very amateur way!

A few nights ago, I watched a programme about the Caribbean. In it, the presenter visited Honduras, a country which quite honestly should be described as a basket case. Crime, particularly violent crime, is through the roof. Gangs have taken over huge swathes of the country – even the prisons are now a gang-stronghold. The presenter walked around the city surrounded by armed guards, all wearing flak jackets.

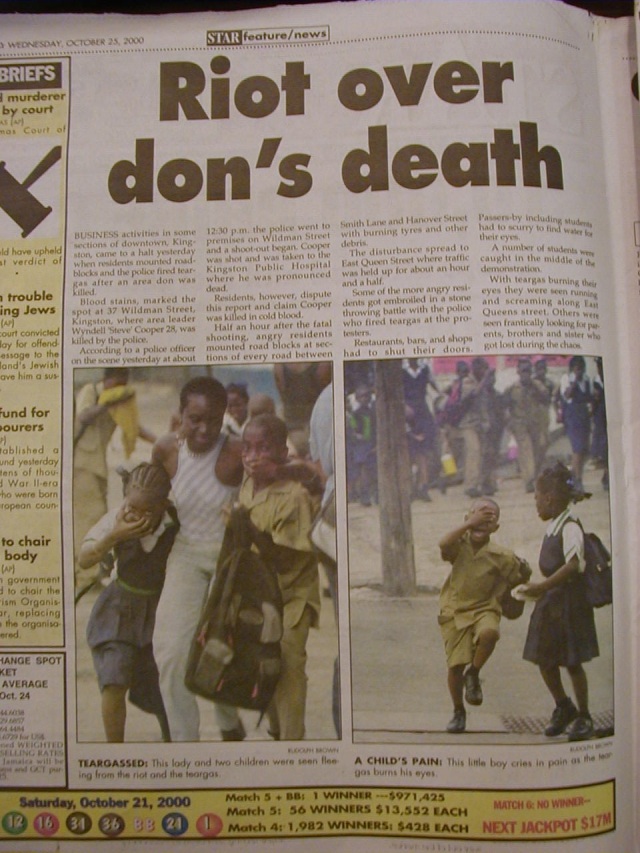

After Honduras, he changed direction and flew to Jamaica. Ah, we were able to sigh, a beautiful, friendly country – what a relief after the madness of Honduras. But ten years ago, when I lived and worked in Kingston, Jamaica was Honduras. It was a country on a one-way road to collapse. The murder rate was one of the highest in the world. Drug gangs made parts of downtown Kingston into total no-go areas. We weren’t able to drive to certain areas unless in armoured cars. The police and the military were riddled with corruption. The economy was plunging, the IMF had been called in. Despite the beautiful beaches and the friendliness of the people, it was a difficult and depressing place to work.

Except, while we were there, we – the UK – along with allies the US, Canada and the EU, started a co-ordinated aid effort to work with Jamaica to try and rescue it from the abyss it was heading towards. Why would we do this? Well mostly because the drugs that were passing through Jamaica on their way from South America were ending up on the streets of London, New York, Toronto. And so their problems were our problems. And our problems were theirs – the desire for cocaine in the west was fuelling the atrocious criminality in the Caribbean.

It really was a coordinated effort. Not only did we work with our American, Canadian and EU friends (as well as the Jamaicans), but it was also coordinated between the different government departments based in the high commission in Kingston. So people who understood the politics talked to the people who understood the police and the gangs. People who understood aid spoke to the people who understood military operations. And all of us spoke to contacts within the Jamaican government law enforcement agencies and civil society groups.

Now lots of things happened that I can’t write about here, and I am sure lots of things happened that I was never even aware of, but I left at a time when a lot of what we were doing was very much still in the early stages. However, even by this point a great amount had been done – we had paid for police officers from the UK to come to work alongside their Jamaican colleagues, mentoring and supporting them. The Department for International Development (DfID) had started working closely with the local civil service to try and bring their astronomical wage bill down – and encourage more people to pay taxes. Law enforcement did their bit and eventually a number of the major players, the “king pins” of the drug gangs were extradited to face charges in the US.

I moved on and lost touch with what was happening in Jamaica. It’s hard to get a perspective when you’re not living there. But the programme we watched the other night was one of the most encouraging things I have seen for a long time. According to the programme makers, the murder rate is down by 40%. FORTY PER CENT. The country is now apparently known as one of the least corrupt in the region. Parts of Kingston that were no-go area are now relatively safe. Youngsters are finding jobs rather than being forced into gangs.

I realise there is a long, long way to go still, and that things could slide backwards as quickly as they seem to have moved forwards. I also realise that the people who really need to take the credit for what has happened in Jamaica are the Jamaicans themselves. But to me this is a major success story. And what it means for us, the people of the UK, is that when Jamaica heals, the drugs stop flowing our way. Which means we all benefit.

This is the story of how foreign aid CAN work, as long as it is targeted and coordinated aid. As long as all the players talk to each other and as long as we work closely with the right people in the host nation.

Whoever wins our election tomorrow, I hope this is one area that doesn’t suffer.

The programme I mention above is Caribbean with Simon Reeve. To watch it please click here.

To read more about the UK’s committment to global development click here.

To read where we stand on Foreign Aid compared to other countries click here

An inspiring piece! Thanks for making me a bit less cynical about foreign aid. As with so many things it seems to be dependent on proper implementation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Don’t get me wrong, there’s still plenty wrong with the way we use our development budget (in my honest opinion) but I don’t think we should give up on it. Rather learn from what works – and also realise that what works in one place won’t always work somewhere else.

LikeLike

Reminds me of the movie The Girl in the Cafe, and how she almost derails the G8 summit in Iceland by making the leaders think about their commitment to combating extreme poverty. Beautiful movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t seen it! Will look out for it, thanks.

LikeLike

Bill Nighy & Kelly McDonald. Bill is just wonderful! I found mine in a charity shop but Amazon has it for £4.99

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Japopupshop and commented:

2015 @trendja

LikeLike

thanks for helping Jamaica we are still fighting the fight. though we smile during the hardest fight corruption…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment and re blogging. I was so happy to see things seem to be improving in Jamaica. So many happy memories of a beautiful country. Ni hope things just continue to get better.

LikeLike

well it seems so, on the brighter side though, you have to make your own way its not easy ill like to show you the help that we has Jamaican need mostly. programs such has https://brianoturner.wordpress.com/2015/05/05/a-ganar-to-win-or-to-earn-motivate-your-community-our-youth/ motivated me through sports and culture. led me to believe in my self check out my video on the program

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thank you so much for your following my blog is about a Jamaican voice i wanna tell the story of the life in Jamaica and its up and down

LikeLike

through out we need motivator like these to get the pedal to the medal

https://brianoturner.wordpress.com/2015/05/05/a-ganar-to-win-or-to-earn-motivate-your-community-our-youth/ pleaes take a look at my video of the programmss that are moving gangs to intelligence just need work experience lol

LikeLike

Fully agree with you, Clara. It’s never going to be perfect but we need to keep plugging away, improving accountability, encouraging bottom up approaches, seeking new solutions. Not easy in the current climate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No it’ll be interesting to see what happens to the foreign aid budget now they’ve declared they’ll give an extra £8billion or whatever it was to the NHS. I suspect the economists at the Treasury will have started sharpening their pencils the moment the exit poll came out!

LikeLiked by 1 person